As in all creative fields, there are groups of people who exchange ideas and must reconcile their ambitions with one another. In most cases, this artistic union gives rise to wonderful surprises and great experiences for consumers.

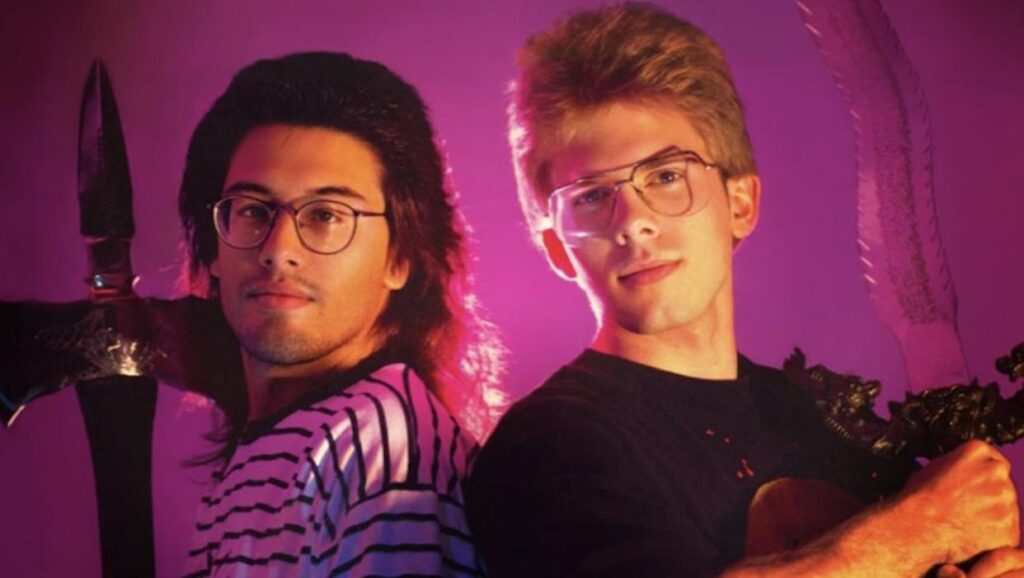

But sometimes disagreements arise… and can even lead to sudden breakups. When we talk about the differences that led to a memorable conflict, it’s impossible not to think of the one between two legends: John Romero and John Carmack. The two developers worked at id Software, where they delivered games that became cult classics in the video game industry.

Whether it was Doom, Doom II, Quake, or Wolfenstein 3D, the duo propelled the FPS genre into a new dimension, creating mechanics that are still used today. And what could be more logical, when you consider that this duo was a rare combination, capable of bringing revolutionary projects to life.

On one side, John Carmack, a genius programmer and coding virtuoso capable of pushing technical boundaries. A rigorous, cold, almost mathematical mind.

On the other, John Romero, flamboyant, charismatic, creative to the core. Game designer, level designer, almost a rock star to the public. A figure as adored as criticized, sometimes judged as overly confident, even narcissistic.

This divisive personality would eventually catch up with him, particularly during the development of Daikatana, where he would burn his wings. But before this disaster, there was a separation, a founding clash: one that arose during the development of Quake.

1996: the beginning of the conflict

At that time, id Software was at its peak. Doom II had shattered sales records, the press was praising the studio, and the two Johns had become stars of PC development. But behind the scenes, tensions were rising.

Carmack wanted to make Quake a technological showcase: a brand new 3D engine, a dark and realistic, almost medieval atmosphere. A demonstration of pure power.

Romero, on the other hand, envisioned a more fun, more fast-paced game, a direct descendant of Doom. He dreamed of fast-paced combat, arcade gameplay, and gentle madness. Two radically opposed visions.

The atmosphere becomes tense. Carmack imposes a military pace of work, with one sleepless night after another. Romero, more scattered, falls behind. He distances himself from the team, preoccupied with his public image. Carmack criticizes him for seeking the limelight. Romero, on his side, does not understand his partner’s lack of flexibility and humanity.

Arguments break out. In front of witnesses. In front of the team. The legendary duo at id Software begins to fall apart.

The separation

When Quake is released in 1996, it’s a success. But it’s a technical success, not a collaborative effort. Romero does not identify with it. Carmack, meanwhile, has lost his teammate. A few months later, Romero leaves id Software. A page has been turned. The studio’s golden age has come to an end.

He founds Ion Storm and launches Daikatana, his crazy project intended to silence the critics. But the development turns into a fiasco. Delays, disorganization, and above all, a disastrous marketing campaign — the famous phrase “John Romero’s about to make you his bitch” becomes a devastating boomerang. The game is released in 2000… in a catastrophic state.

Meanwhile, Carmack continues his work at id Software. He works on Quake III Arena, then on Doom 3, without ever recapturing the magic of the Romero era. The creative momentum has faded.

Two legends reunited

Ironically, despite their separation, the two continue to observe each other. Each influences the other from afar. Carmack remains the visionary engineer. Romero, the passionate artist.

Over time, the resentment fades. In the 2010s, they reconnect, tentatively at first, then more openly. They exchange ideas at conferences and anniversary events. The bitterness is gone.

Romero often says that he no longer feels any resentment. Carmack, for his part, publicly acknowledges that Romero “had played an essential role in the magic of id Software.”

They will probably never work together again. But they talk to each other. They respect each other. And above all, they leave behind a colossal legacy. One of a genre they invented. One of a cult studio. One of an era when two Johns changed the history of video games.

This is a fascinating look at the dynamics between two influential figures in the gaming industry. It’s interesting to see how creative differences can lead to both conflict and innovation. Thanks for sharing this story!

Absolutely, their collaboration in creating groundbreaking games is impressive, but it’s interesting how their differing philosophies on game design ultimately shaped the industry. It’s a reminder that creative tensions can lead to innovation!