After the early promises of how good Intel’s Xe3 GPU architecture could be, thanks to Intel’s breakdown of the changes implemented to everything, we finally got to test one properly last month in the form of a Panther Lake laptop. And you know what? It is good. Very good, in fact.

On paper, that should be a given. Intel’s Arc B390 only sports 1536 shaders, but with 16 MB of L2 cache and a boost clock of 2.5 GHz, that’s way more potent than most integrated GPUs.

Leaving aside AMD’s Ryzen AI Max chips (aka Strix Halo), as they’re less an APU with a big iGPU and more of a small GPU with some CPU chips bolted to it, the most appropriate competition for the B390 is AMD’s Radeon 890M and Nvidia’s GeForce RTX 5050.

I was really curious to see just what the fundamental peak performance of the B390 was like, taking the iGPU out of games and jamming it into some very specific microbenchmarks. However, with neither an 890M nor RTX 5050 to hand, I had to make do with the next best things: the previous generation Radeon 780M and RTX 4050.

The key areas I wanted to look at were: peak instruction throughput, cache and VRAM bandwidth, plus latencies for the latter. They’re not the only things that matter for a GPU, but if these are solid enough, then the rest of the chip’s performance should follow suit.

To that end, I utilised Nemez’s GPUPerfTest, a nifty little project that the developer kindly donated to Chips and Cheese‘s benchmarking suite, and after compiling the latest repo in its GitHub, I set about comparing the three GPUs, plus one more for good measure.

That extra graphics chip is Intel’s first generation of Xe architecture, the Alchemist-powered Arc A770. Rather than radically change the internals with each update, Intel has just consolidated what worked well and improved the weak areas, so in many ways, Xe3 is just a nicely vamped up Xe.

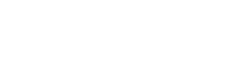

Peak shader throughput

Let’s begin by looking at the peak throughput of a very common instruction in graphics rendering: fused multiply-add, or MADD for short. With this single command, a processor will take two values, multiply them together, and then add the result to a third value. It gets used all the time in graphics rendering, so a good result here is important.

The test repeats the instruction throughput across a range of different data formats, and I’ve selected the ones that are most appropriate here (though INT8 and INT16 are far less of a concern in games than FP32, FP16, and INT32).

Now, it’s important to understand that the result depends heavily on the number of shaders and what clock speed they have. For example, an RTX 4050 has 2560 CUDA cores, boosting up to 1.8 GHz, which gives a theoretical peak FP32 throughput of just under 9 TFLOPS.

As you can see, the RTX 4050 I’ve used is well short of that peak, but that’s because it’s only a 75 W version, so it’s probably not able to sustain its boost clocks long enough. Plus, the test itself doesn’t operate in a theoretically perfect world, so there’s always going to be some differences between reality and paper.

The Arc B390 should be able to hit around 7 or 8 TFLOPS at FP32 and double that figure for FP16. Just like the RTX 4050, it’s well short of those figures, but note how it keeps the Arc A770 in its sights? This is a ‘little’ iGPU keeping up with a full-sized graphics card with a 400 square millimetre GPU.

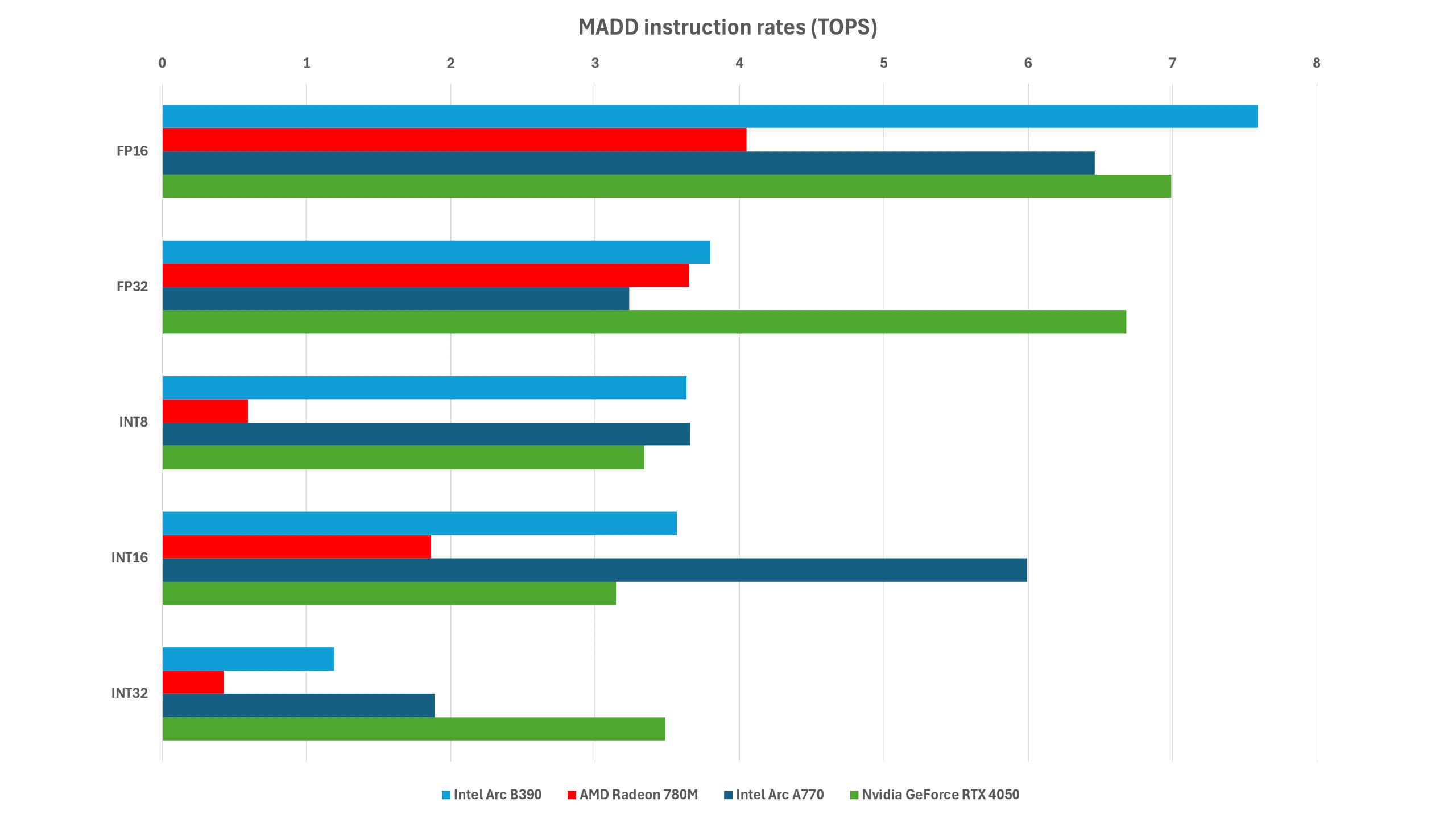

Cache and memory bandwidth

The next test I ran was one that essentially measures the peak data throughput, for different data sizes, with all the GPU’s shaders kept busy demanding said data. It’s not only useful to see how well the processor can keep its logic units fed with information, but it also gives you a clear indication of cache sizes.

Where the lines go from being flat to taking a nose down marks the rough boundary of how big the various cache sizes are. Not entirely so, because drivers are often a bit funny about how they interpret Vulkan instructions (the API used for the test), and in some cases, the cache is an adjustable shared memory, rather than being fixed in size.

The more pipelines a GPU has, the greater the initial bandwidth will be, which is why the 4096-shader A770 is way above the tiny B390, 780M, and RTX 4050. However, the clock speed of the caches also matters, and this is why the Xe3 iGPU does so well here, faring nicely against the little Nvidia chip.

But it’s even more impressive when you realise there are relatively few shaders in the B390. Yes, they’re clocked pretty high, but pulling 6 TB/s from the L1 cache suggests that it has a very wide internal data bus. You’d expect that with a big dGPU, not a teeny iGPU.

One surprise, though, is just how poor the Radeon 780M is in the test. AMD uses a clever, if complex, cache system to maximise data flow throughout the GPU, but you wouldn’t think that here, looking at these results. What I suspect is that the problem is that this particular iGPU is that of an Asus ROG Ally, a device that gets driver updates on a very slow cadence.

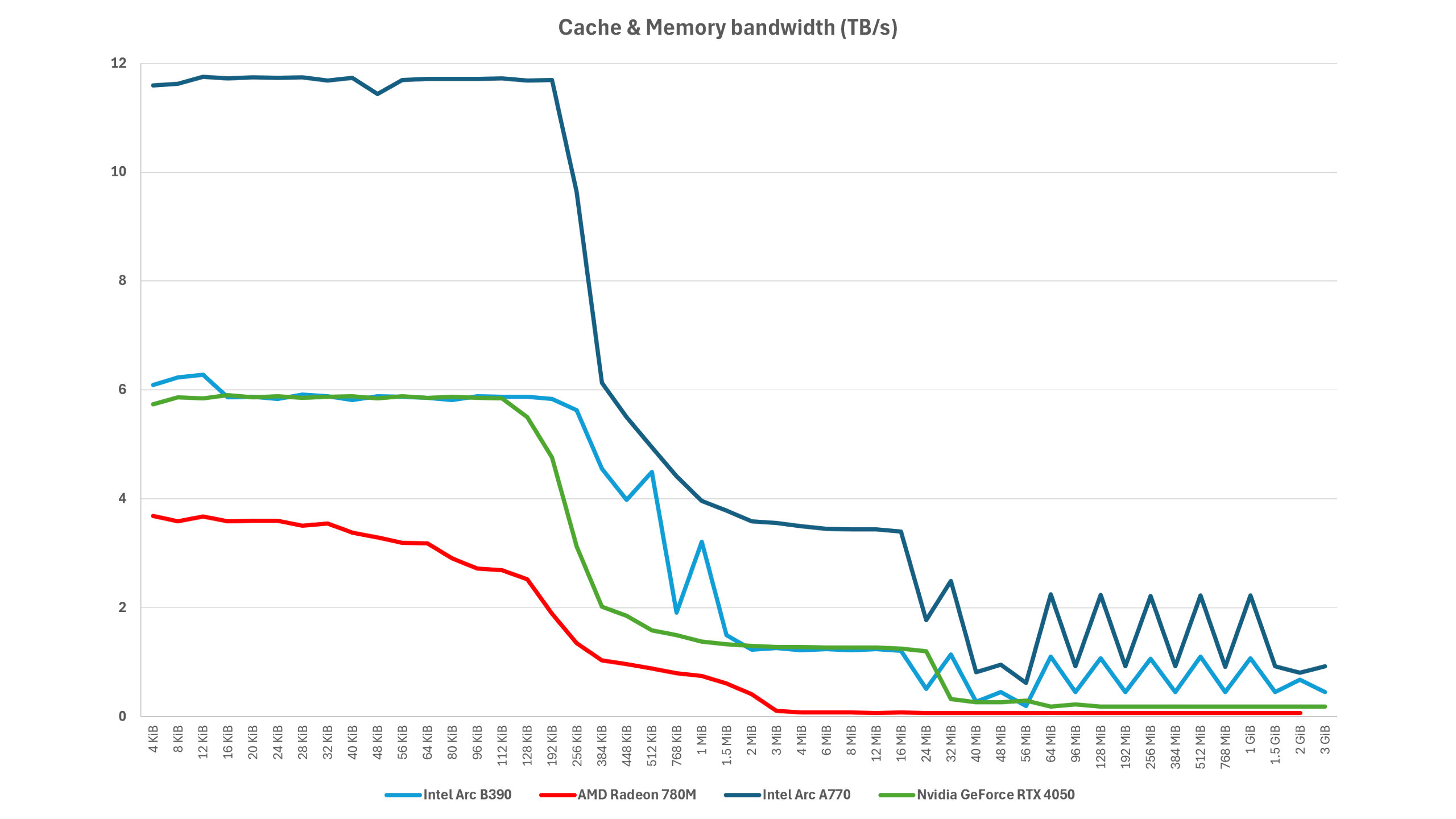

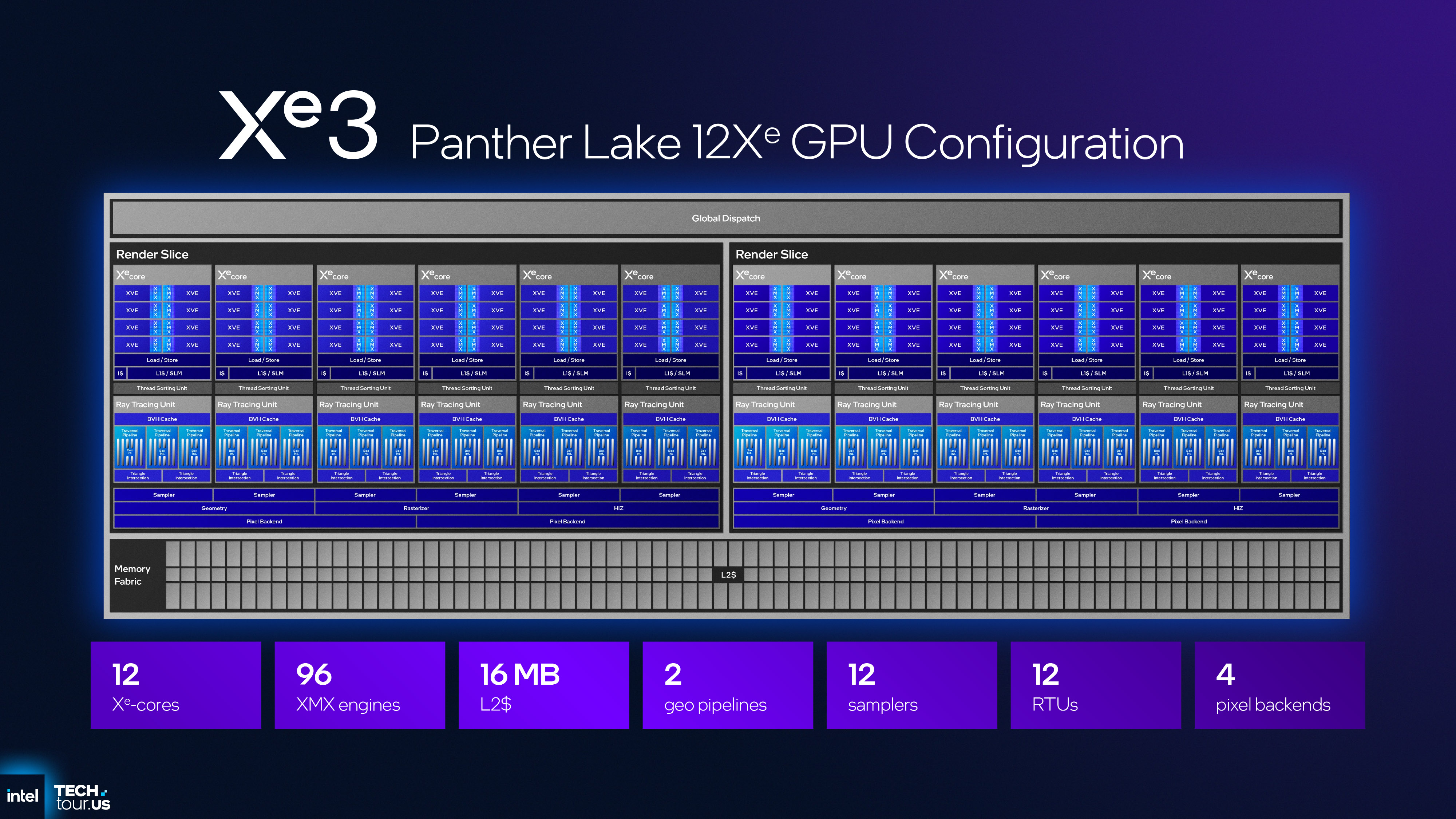

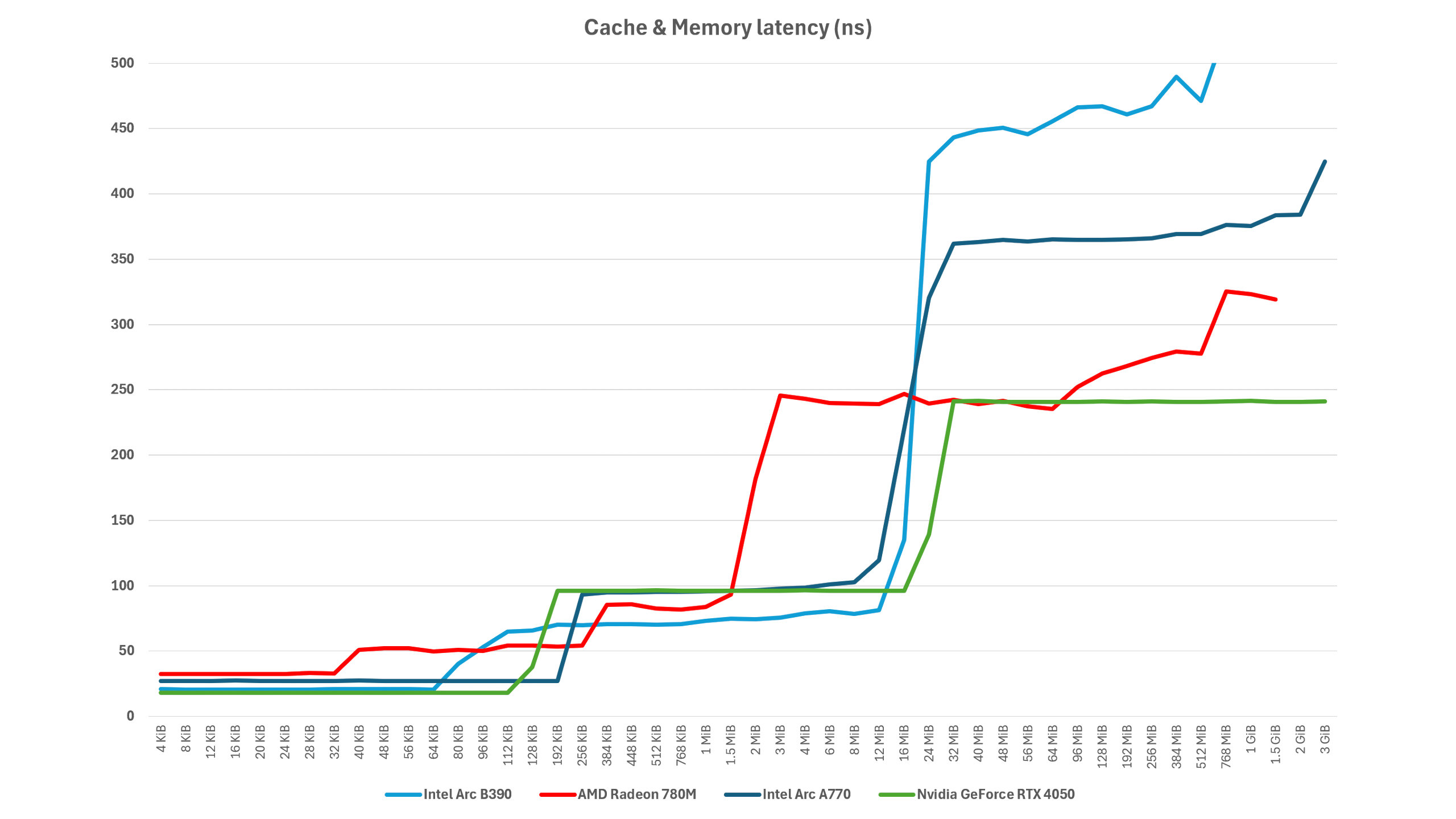

Cache and memory latency

Having lots of internal bandwidth is all well and good, but if the GPU’s cache system takes a long time to respond to data requests, then all it will do is stall shader pipelines that have requested said data (with the end result being a reduction in performance).

So the final test I ran was looking at the cache latency: the time in nanoseconds between a data request being issued and the data being delivered. Architecture is important here, but so too are clock speeds. Just as before, where the lines change from flat to going up is where you can glean how large the caches are.

In the case of the Arc B390 it has a pretty swift L1 cache, but it actually reported the lowest L2 latencies of all the chips I tested, coming in well under the RTX 4050 and Arc A770. Unfortunately, the final stages of the graph shows Xe3’s biggest weakness: the use of LPDDR5x.

Where the Arc A770 and GeForce RTX 4050 both use dedicated GDDR6 modules, the Arc B390 has to use system memory for its VRAM, and not only is LPDDR5x a bit sluggish (in terms of latencies), that memory also has to contend with instructions from the rest of the system.

However, note how poor the A770’s VRAM latencies are compared to the RTX 4050, despite using exactly the same type and speed of GDDR6? Sure, the B390 is worse (and much worse compared to the 780M which is also using system-shared LPDDR5x), but it’s superior all round until the data requests hit the DRAM.

Xe3’s strengths and weaknesses

Three small microbenchmarks aren’t enough to glean a full insight into the inner workings of a processor, but they’re enough to get an inclination as to what’s good and bad about the Xe3 architecture in the Arc B390.

Basically, it’s all good bar one thing: the lack of dedicated VRAM. Or rather, how well Intel’s drivers and firmware currently handle data flows between the shared system memory and the iGPU. There’s a decent amount of bandwidth on tap from using fast LPDDR5x, but those DRAM latencies aren’t exactly great, and I suspect that stops the Arc B390 from being able to reach its full potential in some games.

But just imagine a big Xe3 GPU, in a proper discrete graphics card with lots of high-speed GDDR7 memory. That would certainly give AMD and Nvidia something to fret over if it ever came to market, but Intel is in no rush to bring anything like that to market. There’s talk of an Xe3-variant, X3P, being used for Intel’s next generation of Arc graphics cards, but Team Blue’s been pretty tight-lipped about it all.

The architecture is good, great even; it just deserves a better home than a laptop processor, no matter how nice it is.